As Halloween and Samhain draw near, I’m thinking a lot about the cemeteries I’d like to visit. All of them are places where my ancestors are buried; I’ve also got a long mental list of “destination” cemeteries where nobody I know is buried. Maybe that’s a post for another day.

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, New York

One of my ancestral lines that I’ve been able to trace back quite far is the Storm family, who lived in the Netherlands for many generations before Dirck Goris Storm (1630-1716), my 10th great-grandfather, immigrated to the U.S. in 1662. He eventually wound up in a new, small town called North Tarrytown on the eastern banks of the Hudson River, and later wrote the history of the Old Dutch Church in North Tarrytown. A man after my own heart.

I wrote a longer post about him in 2020, but he died long before Washington Irving came to visit and made the town famous. It later officially changed its name to Sleepy Hollow and the old cemetery (pictured above), where many Storms are buried, has become a tourist attraction. I recently learned, thanks to my friend Loren Rhoads, that the Ramones filmed their video for “Pet Sematary” here, too.

White House family graveyard, Virginia

The White House in Luray, Virginia. Photo courtesy the Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

Another cluster of my ancestors were Mennonites who immigrated to the U.S. from Switzerland in the early 1700s, settled in Pennsylvania for a couple of generations, and then established a community in the Shenandoah Valley in a place now called Luray. My fifth great-grandfather, Martin Kauffman, Jr., built a meetinghouse called the White House that still stands today.

A small family graveyard was established next to the White House, where several of my ancestors and their families were buried. I recognize so many names on the gravestones: Brubaker, Roads, Albright, Strickler and Martin himself, along with his father, Martin Kauffman Sr.

Downpatrick Second Presbyterian Church, Northern Ireland

My second great-grandfather, James Corry Nesbitt, came to the U.S. in 1866 (three of his brothers also immigrated within about a decade of each other). But the rest of his family remained in Northern Ireland, particularly in and around a small region called Tyrella.

There’s a memorial stone to these ancestors in the churchyard of the Second Presbyterian Church in Downpatrick, including James’ parents, William Nesbitt and Margaret Corry; his siblings, George, Alexander and Robert, and his grandparents, Robert Nesbitt and Jane Cochrane. There are markers for 24 Nesbitts here, and I’m probably in some way related to all of them. James Corry Nesbitt, his wife, Elizabeth Woollard and their kids are buried in Green Lawn Cemetery in Franklin County, Ohio; another stop on my wishlist.

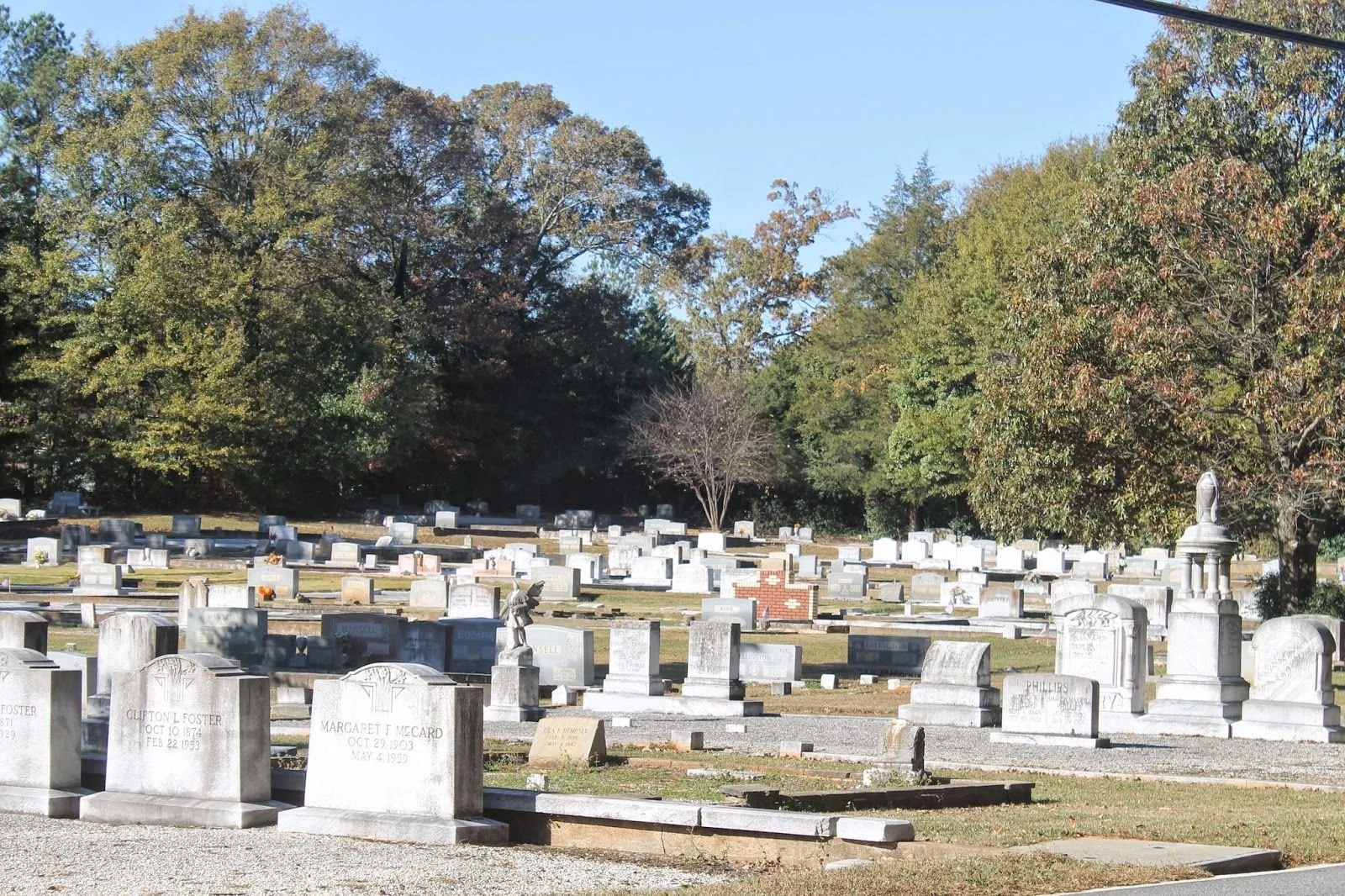

Old Roswell Cemetery, Georgia

My second great-grandfather, Zachary (or Zachariah) Taylor Jones, Sr., was a significant patriarch on my mom’s side. He was the second-oldest of 10 children, born in 1849 in Roswell, Georgia, where he lived his entire life. He worked as a farmer and also served as the town constable. He married three times and fathered a total of 19 children.

He’s buried in the Old Roswell Cemetery, along with all three of those wives (Mamie Hunnicutt, Alice Bruce, and my second great-grandmother, Lucretia “Cressy” Perkins) and most or all of his children, including my great-grandfather, Bartow Jones. I’m especially grateful to the Roswell Historical Society’s Cemetery Project, which is restoring and replacing grave markers with the help of donations.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this quick virtual tour. What cemeteries — ancestral or otherwise — would you like to visit?