Blacks who are descended from enslaved people face unfair challenges when they try to trace their ancestry. It wasn’t until the 1870 census, in the United States, that many enslaved black Americans were counted as free people, and by their first and last names. Before that, the genealogical path becomes one of piecing together the 1860 and 1850 slave schedules and the wills or sale receipts of their enslavers, who may have listed them only by first name and age.

Much of my maternal line came over from Western Europe and settled in the Southern part of the U.S. by the early 1700s, and almost every branch includes one or more enslavers. I’ve done my best to document these enslavers, and the people they enslaved, in the hope that it might make the road easier for their descendants, hoping to find out more about where and who they came from.

The information in this post is everything I have been able to find, to date, on these people, but please reach out if you have questions.

For more help researching enslaved ancestors, I highly recommend the Facebook group I’ve Traced my Enslaved Ancestors and their Owners.

The names of the following enslaved people are listed in this document:

Adaline (John Gann will, 1858, Clarke County, Georgia)

Alexander (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Alice (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Ami (John Gann will, 1858, Clarke County, Georgia)

Anderson (baby; unclear if this is a first or last name) (William Gann will, 1852, Clarke County, Georgia)

Ann (Isaac Bradley will, 1848, Greenville County, South Carolina)

Betsey (Amos Banks will, 1843, Lexington County, South Carolina)

Caroline (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

Cato (Thomas Kimbrough will, 1777, Caswell County, North Carolina)

Caty (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Ceeser (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Chaney Gann (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

Charity (John Gann will, 1858, Clarke County, Georgia)

Charlotte (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Ciciro (John Gann will, 1858, Clarke County, Georgia)

Clary (Abraham Bradley will, 1823, Greenville County, South Carolina)

David (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Dick (Mary Polly Thomas will, St. Peters, Pennsylvania)

Elic (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

Emeline (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Emily (Isaac Bradley will, 1848, Greenville County, South Carolina)

Emily (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

Esther (George Long will, 1815, South Carolina)

Flora (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Frank (John Gann will, 1858, Clarke County, Georgia)

Gabe (Thomas Kimbrough will, 1777, Caswell County, North Carolina)

George (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

George (John Gann will, 1858, Clarke County, Georgia)

George (Thomas Kimbrough will, 1777, Caswell County, North Carolina)

Hannah (Jeremiah Jackson will, 1825, Greene County, Georgia)

Harry (Jeremiah Jackson will, 1825, Greene County, Georgia)

Hegor (woman) (Mary Polly Thomas will, St. Peters, Pennsylvania)

Henry (Isaac Bradley will, 1848, Greenville County, South Carolina)

Henry (John Gann will, 1858, Clarke County, Georgia)

Henry (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

Isaac (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Isaac (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

Jane (John Gann will, 1858, Clarke County, Georgia)

Jenny (Thomas Kimbrough will, 1777, Caswell County, North Carolina)

Jesse (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Jim (Isaac Bradley will, 1848, Greenville County, South Carolina)

Jim (John Gann will, 1858, Clarke County, Georgia)

Joe (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

John (William Gann will, 1852, Clarke County, Georgia)

Jude (girl) (William Kimbrough will, 1803, Greene County, Georgia)

Julia (William Gann will, 1852, Clarke County, Georgia)

Kezia (Isaac Bradley will, 1848, Greenville County, South Carolina)

Lewis (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

Lewis (John Gann will, 1858, Clarke County, Georgia)

Linda (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

Lucy (William Gann will, 1852, Clarke County, Georgia)

Lucy (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

Lydden (Thomas Kimbrough will, 1777, Caswell County, North Carolina)

Margaret (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Martha (John Gann will, 1858, Clarke County, Georgia)

Mary Gann (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

Micah (John Gann will, 1858, Clarke County, Georgia)

Milly (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

Mimi (William Kimbrough will, 1803, Greene County, Georgia)

Mira (George Long will, 1815, South Carolina)

Monica (Isaac Bradley will, 1848, Greenville County, South Carolina)

Ned (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

Nancy (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Oliver (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

Parker (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Patience (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

Peter (Jeremiah Jackson will, 1825, Greene County, Georgia)

Peter (John Gann will, 1858, Clarke County, Georgia)

Phebee (Thomas Kimbrough will, 1777, Caswell County, North Carolina)

Polly (Amos Banks will, 1843, Lexington County, South Carolina)

Rachel (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Rebeckah (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Ritty/Rithy (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Sam (George Long will, 1815, South Carolina)

Sam (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Sam (Thomas Kimbrough will, 1777, Caswell County, North Carolina)

Sandy (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Sarah (George Long will, 1815, South Carolina)

Serlla (John Gann will, 1858, Clarke County, Georgia)

Silas (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Silvey (William Kimbrough will, 1803, Greene County, Georgia)

Solomon (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

Suiey (Thomas Kimbrough will, 1777, Caswell County, North Carolina)

Susanah (Amos Banks will, 1843, Lexington County, South Carolina)

Thomas (Thomas Gillespie will, 1838, Rowan County, North Carolina)

Tom (a blacksmith): sold by Amos Banks to Michael Long on May 23, 1843, Edgefield, South Carolina

Tom (William Gann will, 1852, Clarke County, Georgia)

Vilda (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

William (William Gann will, 1852, Clarke County, Georgia)

Willis (Ignatius Nathan Gann will, 1854, Dallas, Paulding County, Georgia)

Listed in this document are the following enslavers. Details are below:

Amos Banks, 1777-1843, Lexington County, South Carolina

Charles Banks, 1747-1830, Charleston, South Carolina

Abraham Bradley, 1737-1823, Greenville County, South Carolina

Isaac Bradley, 1785-1847, Greenville County, South Carolina

Daniel Ashley Bruce, 1807-1891, Greenville County, South Carolina

John T. Frey, 1802-1854, Lexington County, South Carolina

Henry “Granser” Gann, 1816-1914, Clarke County, Georgia

Ignatius Nathan Gann, 1785-1854, Clarke County, Georgia

John Gann, Sr., 1770-1856, Clarke County, Georgia

Nathan Gann III, 1821-1900, Paulding County, Georgia

William Gann, 1794-1853, Clarke County, Georgia

Malachi Green, 1790-1879, Martin County, North Carolina

Thomas Gillespie, 1770-1838, Abbeville County, South Carolina, and Gordon County, Georgia

Daniel E. Jackson, 1796-1869, DeKalb County, Georgia

Jeremiah Jackson, 1760-1828, Greene County, Georgia

John H. Jones, 1802-1886, DeKalb County, Georgia

Thomas Kimbrough, 1690-1777, Caswell County, North Carolina

William Kimbrough, 1735-1803, Caswell County North Carolina

George Long, 1758-1815, Edgefield, North Carolina

Hugh McLin, 1749-1843, Abbeville County, North Carolina

John Henry Segars, 1733-1806, Wake County, North Carolina and Darlington County, South Carolina

John Summers, 1762-1848, Hillsboro, North Carolina and Clarke County, Georgia

Mary Polly Thomas, 1694-1771, Chester County, Pennsylvania

My fifth great-grandfather, Amos Banks, was born May 11, 1777 in Lexington, South Carolina and died February 6, 1843 in Lexington, South Carolina.

In the 1820 census, he is listed as enslaving one person, a man between the ages of 26 and 44 in Lexington, South Carolina.

In the 1830 census, he is listed as enslaving 13 people: one boy between the ages of 10 and 23, three men between the ages of 24 and 35, two men between the ages of 36 and 54, one girl under 10, two girls between the ages of 10 and 23, two women between the ages of 24 and 35, and two women between the ages of 36 and 54, in Lexington, South Carolina.

In the 1840 census, he is listed as enslaving 11 people: two boys under age 10, two boys between the ages of 10 and 23, two men between 24 and 35, one man between 36 and 54, one girl under 10, one girl between 10 and 23, one woman between 24 and 35, and one woman between 36 and 54, in Edgefield, South Carolina.

The March, 1843, slave records say that Amos Banks sold a black man named Tom, a blacksmith, to Michael Long for $375. The sale took place in Edgefield, South Carolina, on May 23, 1843. Michael Long was likely the brother of Amos Banks’ wife, Catherine.

In his 1843 will, Amos Banks left his wife, Catherine (maiden name Long), “one negro girl named Polly,” and his son, Thomas, “consideration of two negroes, Susanah and Betsey, which I sold to Drury Fort.”

My sixth great-grandfather, Charles Banks, Jr. was born June 10, 1747, in Prince George, Virginia, and died January 26, 1830, in Lexington County, South Carolina. He was the father of Amos Banks.

In the 1800 census, he is listed as enslaving 7 people in Charleston, South Carolina.

In the 1810 census, he is listed as enslaving 9 people in Charleston, South Carolina.

In the 1820 census, he is listed as enslaving 7 people in Charleston, South Carolina.

In the 1830 census, he is listed as enslaving 2 girls between 10 and 23 years of age, two women between 24 and 35 years of age, and one boy under age 10.

My sixth great-grandfather, Abraham Bradley, was born in 1737 in Orange County, Virginia and died on October 23, 1823, in Greenville, South Carolina. He was the father of Isaac Bradley.

In the 1790 census, he is listed as enslaving one person in Greenville, South Carolina.

In the 1800 census, he is listed as enslaving 4 people in Greenville, South Carolina.

In the 1810 census, he is listed as enslaving 8 people in Greenville, South Carolina.

In the 1820 census, he is listed as enslaving 4 people: one boy under 14, two men between the ages of 26 and 44, and one woman 45 or older, in Greenville, South Carolina.

In his 1823 will, he left his wife, Sarah Elizabeth Bradley (maiden name Lane), “one negro girl named Clary and a child.”

My fifth great-grandfather, Isaac Bradley, was born in 1785 in Orange, North Carolina and died in 1847 in Greenville, South Carolina. He was the son of Abraham Bradley, listed above.

In the 1820 census, he is listed as enslaving one person, a boy between age 14 and 25, in Greenville, South Carolina.

In the 1830 census, he is listed as enslaving one person, a boy between age 10 and 23, in Greenville, South Carolina.

In the 1840 census, he is listed as enslaving three people, two girls under 10 and one girl between 10 and 23, in Greenville, South Carolina.

In his 1848 will, he left his wife, Sarah Armstrong (my fifth great-grandmother), two girls named Emily and Monica. He left Daniel Bruce (his son-in-law, and my fourth great-grandfather) a girl named Ann. He left James McAdams a woman named Kezia and her child (no name recorded). To TJ Dean he left a boy named Jim, and to ES Irvine he left a boy named Henry.

My fourth great-grandfather, Daniel Ashley Bruce, was born March 3, 1807, in Wolfcreek, Pendleton County, South Carolina and died in 1891 in Greenville County, South Carolina. He served in the Confederate Army.

In the 1850 slave schedule, he is listed as enslaving a 5-year-old girl. This may be Ann, the girl he inherited from his father-in-law, Isaac Bradley, listed above.

My fourth great-grandfather, John T. Frey, was born October 2, 1802, in Lexington, South Carolina, and died June 27, 1854, in Lexington, South Carolina.

In the 1840 census, he is listed as owning one slave, a man between age 24 and 35, in Lexington, South Carolina.

My fourth great-grandfather, Malachi Green, was born April 16, 1790, in Bertie County, North Carolina, and died April 9, 1879, in Martin County, North Carolina.

In the 1860 slave schedule, he is listed as enslaving one person, a 56-year-old man.

My fourth great-uncle, Henry “Granser” Gann, was born February 28, 1816, in Georgia, and died on February 24, 1914, in Cobb County, Georgia. He served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War and was discharged in November of 1862 for an unspecified disability. His father was my fifth great-uncle, Ignatius Nathan Gann, who’s listed below.

In the 1850 census, he is listed as enslaving seven people, including a 10-year-old boy, a boy between the ages of 10 and 23, two men between 24 and 35, two girls under 10, and a girl between 10 and 23, in District 240, Clarke County, Georgia.

My sixth great-uncle, Ignatius Nathan Gann, was born in 1786 in Athens, Georgia, and died June 5, 1854, in Dallas, Georgia. His wife was Nancy Summers, daughter of my fifth great-grandfather, John Summers, who is listed below.

In the 1830 census, he is listed as enslaving 10 people, including a boy between the ages of 10 and 23, two men between 36 and 54, two girls under 10, two girls between the ages of 10 and 23, two women 24 to 35 and one woman between 36 and 54, in Clarke County, Georgia.

His 1854 will includes the sale of the following people:

Chaney, a woman about 36 years old*

Isaac, a man about 40 years old

Mary and her child Henry**

Vilda

Patience and her infant Lucy**

Milly and her child Willis

Linda

Joe

Caroline

Solomon

Oliver

Ned

Emily

George

Lewis

[and a few names I can't read]

*Chaney was written about after she was freed; she lived to be more than 110 years old.

**The Mary mentioned here was likely Chaney's daughter, and Patience is Mary's daughter (Chaney's granddaughter)

In a separate bill of sale, it says:

Chaney was sold to William D. Gann

George was sold to John Gann

Lewis was sold to George Rice

Elic was sold to William Adair

My fifth great-grandfather, John Gann Sr., was born in 1770 in North Carolina and died in 1856 in Clarke County, Georgia. He was the father of William Gann (1794-1852).

He is listed in the 1830 census as enslaving five people, including two boys aged 10 to 23, two girls aged 10 to 23, and a woman aged 24 to 35, in Clarke County, Georgia.

He is listed in the 1840 census as enslaving three people, a boy between the ages of 10 and 23, a man between 36 and 54, and a girl between 10 and 23, in Vinson, Georgia.

In his will, which was probated in September of 1858 in Clarke County, Georgia, the following people are listed for sale:

Ami & son George

Jane & children Lemis, Micah, Serlla

Kate & five children, Martha, Henry, Jim, Ciciro, & infant Frank

Adaline

Charity

Peter

Nathan Gann III, the son of my sixth great-uncle, was born October 17, 1821, in Clarke County Georgia and died sometime after 1900, likely in Saint Clair County, Alabama.

In the 1860 slave schedule, he is listed as enslaving a 39-year-old mulatto woman in District 1080, Paulding, Georgia.

My fourth great-grandfather, William Gann, was born in 1794 in Athens, Georgia, and died in 1853 in Clarke County, Georgia.

In the 1840 census he is listed as owning seven slaves, including a boy between the ages of 10 and 23, a man between 24 and 35, three girls under 10, one girl between 10 and 23, and one woman between 24 and 35, in District 240, Clarke County, Georgia.

In his 1852 will, a number of people are listed for sale, including:

Julia and her child, Anderson

John, 10 years old

Lucy, 8 years old

William, 4 years old

Tom, about 55 years old

My fourth great-grandfather, Thomas Gillespie, was born in 1770 in Abbeville, Abbeville County, South Carolina and died September 7, 1838 in Gordon County, Georgia.

In the 1800 census, he is listed as enslaving one person in Abbeville County, South Carolina.

In the 1820 census, he is listed as enslaving a girl under the age of 14 in Abbeville County, South Carolina.

According to Thomas Gillespie’s 1838 will, however, he enslaved more than 20 people. He had sorted them into “lots” and left them to the following individuals:

“Lot 1”: Thomas, Caty and Silas to Richard Gillespie

“Lot 2”: Rachel and Jesse to Flora Gillespie

“Lot 3”: Isaac and Emeline

“Lot 4”: Sandy and Rebeckah to John Gillespie

“Lot 5”: Parker and Margaret to McCoy Gillespie

“Lot 6”: Ritty/Rithy and Alexander to George Gillespie

“Lot 7”: Alcie or Alice and Alexander to Archibald Gillespie

“Lot 8”: Nancy, Ceeser/Ceaser and Robert to William Gillespie

“Lot 9”: Charlotte, Sam and David to Christopher Graham

My fourth great-grandfather, Daniel E. Jackson, was born January 5, 1796, in Georgia and died August 11, 1869 in DeKalb County, Georgia. He was the son of Jeremiah Jackson, below.

In the 1820 census, he is listed as enslaving two people, a man between the ages of 26 and 44, and a girl between the ages of 14 and 25, in Captain Allen’s District in Greene County, Georgia.

In the 1830 census, he is listed as enslaving a girl under 10 and a girl between the ages of 10 and 23 in Walton County, Georgia.

In the 1850 slave schedule, he is listed as enslaving a 23-year-old mulatto woman, a 12-year-old black boy, a 10-year-old black girl and a one-year-old mulatto boy, in the Andersons District of DeKalb County, Georgia.

In the 1860 slave schedule, he is listed as enslaving a 31-year-old mulatto man, a 21-year-old black man and an 11-year-old mulatto boy in DeKalb County, Georgia.

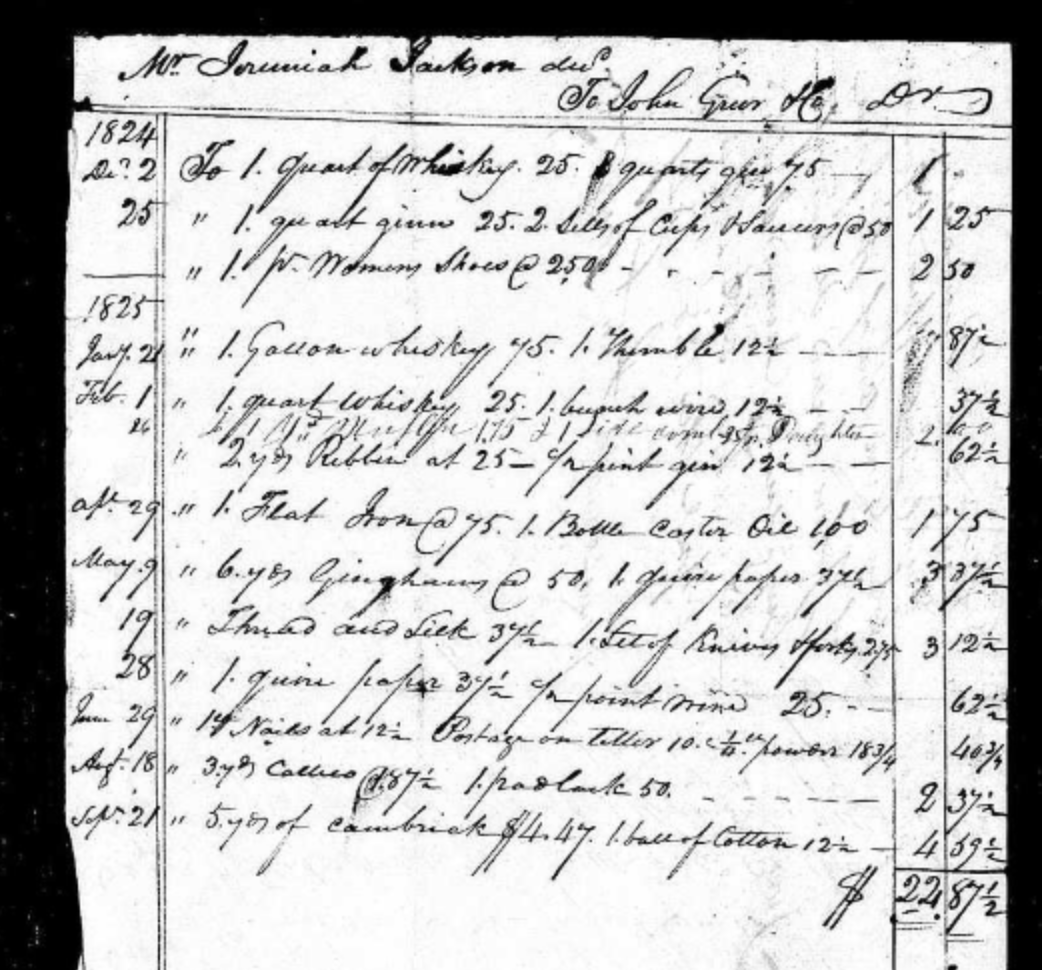

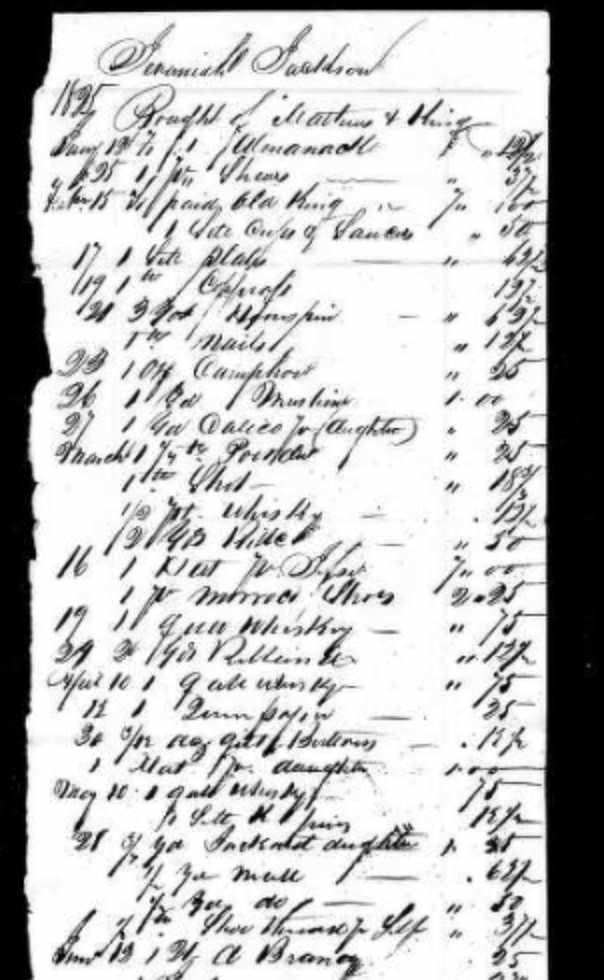

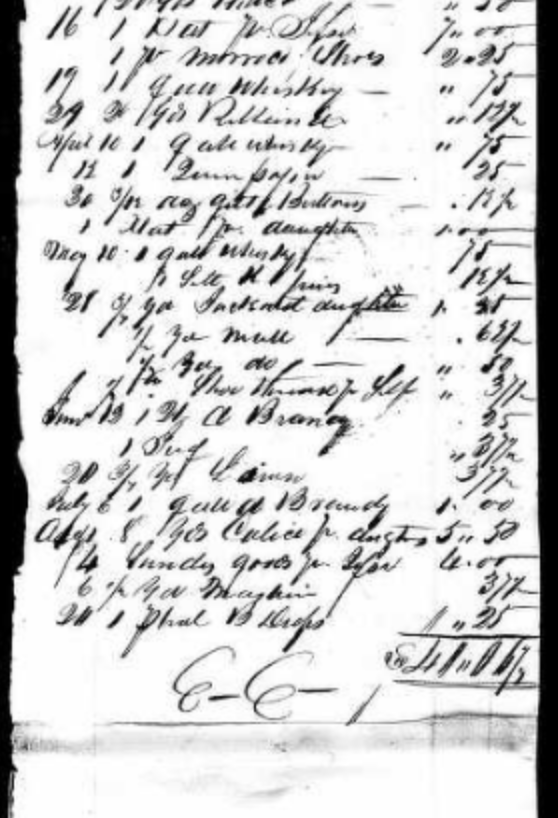

My fifth great-grandfather, Jeremiah Jackson, was born August 18, 1760 in Bedford County, Virginia and died September 21, 1828 in Greene County, Georgia. He was the father of Daniel E. Jackson, above.

In his 1825 will, he leaves “to my little daughter Sarah ... a negro woman named Hannah and her two children, Harry and Peter,” and “to my children Daniel E., Nelson, Diana, Irene and Elizabeth ... the balance of my negroes stock.” His will was probated in Greene County, Georgia.

My third great-grandfather, John H. Jones, was born August 8, 1802 in South Carolina and died January 12, 1886 in Atlanta, Georgia. In 1822, he married Polly Gillespie in South Carolina. Her father, Thomas Gillespie, is listed above.

In the 1830 census he is listed as enslaving a boy between the ages of 10 and 23 in DeKalb County, Georgia.

In the 1860 slave schedule he is listed as enslaving a 57-year-old black woman in DeKalb County, Georgia.

My seventh great-grandfather, Thomas Kimbrough, was born in 1690 in New Kent, Virginia, and died September 20, 1777, in Caswell County, North Carolina. He was the father of William Kimbrough, listed below.

A number of people he enslaved are listed in his wills, which were probated in 1777 in Caswell County, North Carolina:

Sam

George

Cato

Suiey

Phebee

Jenny

Gabe

Lydden and infant

My sixth great-grandfather, William Kimbrough, was born in 1735 in Caswell County, North Carolina and died in 1803 in Caswell County, North Carolina. He is the son of Thomas Kimbrough, listed above.

In the 1800 census, he is listed as owning two slaves in Hillsboro, Caswell County, North Carolina.

In his 1803 will, which was probated in Greene County, Georgia, William Kimbrough left his wife, Mary (maiden name Gracey) a girl named Silvey; he left his son, William Jr., a girl named Jude, and his grandson, Thomas, a girl named Mimi.

My 6th great-grandfather, George Long, was born in 1758 in Newberry County, South Carolina, and died July 6, 1815 in South Carolina (probably in Edgefield).

In the 1800 census, he is listed as enslaving two people in the Newberry District in South Carolina.

In the 1810 census, he is listed as enslaving five people in Edgefield, South Carolina.

In his 1815 will, he leaves a man named Sam and a woman named Mira, along with two children named Esther and Sarah, to his wife, Catherine (maiden name Moyers).

My fifth great-grandfather, Hugh McLin, was born in 1749 in North Carolina and died on November 7, 1843, in Abbeville County, South Carolina. His daughter, Anna McLin, married Thomas Gillespie, listed above. His granddaughter, Polly Gillespie, married John H. Jones, also listed above.

He is listed in the 1830 census as enslaving a boy between the ages of 10 and 23, in Abbeville County, South Carolina.

My 6th great-grandfather, John Henry Segars, was born January 17, 1733 in Raleigh, North Carolina and died November 26, 1806 in Darlington County, South Carolina.

He is listed in the 1790 census as enslaving three people, genders and ages unknown, in Wake County, North Carolina.

He is listed in the 1800 census as enslaving six people, genders and ages unknown, in Darlington County, South Carolina.

My fifth great-grandfather, John Summers (Somers), was born May 26, 1762, in Fairfax County, Virginia, and died September 23, 1848 in Cobb County, Georgia. His wife, Mary Kimbrough, was the daughter of William Kimbrough, listed above. His daughter, my fourth great-grandmother Elizabeth “Dolly” Summers, married William Gann, listed above.

In the 1800 census, he is listed as enslaving four people in Hillsboro, Caswell County, North Carolina.

In the 1830 census, he is listed as enslaving two boys between the ages of 10 and 23 in Clarke County, Georgia.

My seventh great-grandmother, Mary Polly Thomas (maiden name Griffiths) was born in 1694 in Chester County, Pennsylvania, and died on September 30, 1771, in St. Peters, Pennsylvania.

In her 1771 will, she left a man named Dick to her son, William Thomas, an unnamed “negro lad” to her son, Benjamin Thomas, and to her daughter, Sarah Marin, a woman named Hegor.