My dad and uncles grew up in an unusual house in Worthington, Ohio, located at 382 West Wilson Bridge Road. It was more than large enough for my grandparents and their five boys, and provided ample room to run around and explore. Just before the property was torn down to make way for a freeway, Columbus Dispatch reporter Bill Arter and photographer Jack Hutton visited the property to capture images of the unusual series of caverns and tunnels under the property, built by inventor Thomas Midgley. Read the full article below.

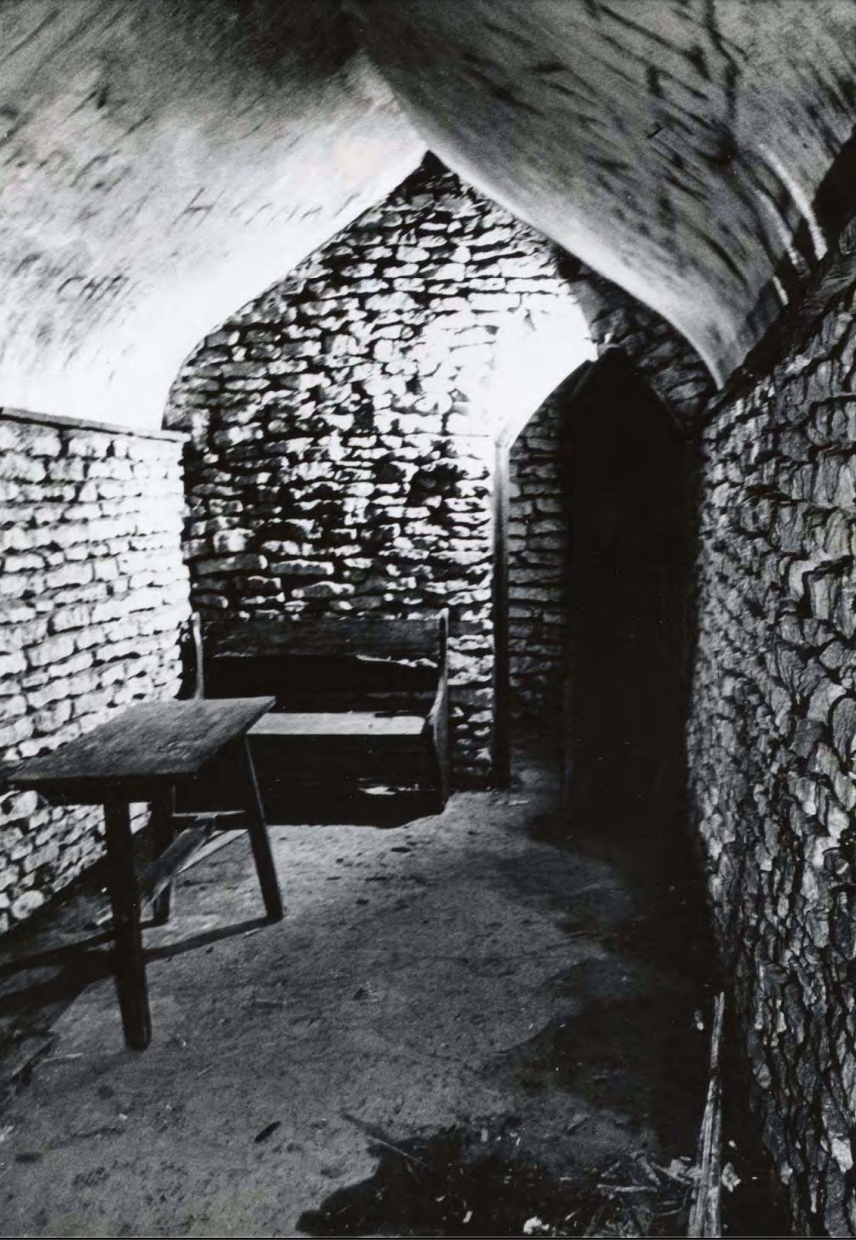

Worthington house tunnels, mid-level exit.

MAN-MADE CAVERN

By Bill Arter

Photos by Jack Hutton

Columbus Dispatch Magazine

Sunday, October 31, 1965

THERE'S this big stone wall with a great big solid-oak door with great, huge iron hinges and iron all over it, right down at the bottom of the bluff in the woods." Thus, all in a rush and with little by way of introduction, began my young son. At least he was young then; it's been more than 20 years ago. Having caught my interest, he proceeded from allegedly observed fact to hearsay: "The kids say it leads into a cave that runs all around and has big stone rooms and everything and finally runs right up into that rich guy's basement.". "What rich guy?" I asked, more or less idly, being convinced that young Bill had been having his leg pulled. "The guy that invented Ethyl gas," he replied. “You know, the big white house with the swimming pool that sets way back from Wilson Bridge Road."I began to feel a flicker of interesting hope that this wonderful tale might be true.

Certainly our neighbor, Tom Midgley, could afford a private cavern, if he wanted it. And, as it turned out, he had wanted it and he did have it every bit as grand as the description. Thomas Midgley came by his inventiveness naturally. His father, born in London, England, was an inventor and natural mechanic who contributed a great deal to the development and manufacturing of bicycles. He came to America at an early age and was living in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania when Thomas was born May 19, 1889. The family soon moved to Columbus where his father became superintendent of the old Columbus Bicycle Company. Young Tom grew up here; he attended Hubbard and Fifth Avenue schools and graduated from old North High School.

He went on to graduate from Cornell in 1911 with a degree in mechanical engineering. Surprisingly, his most significant inventions were in another field altogether--in chemistry.

Tom's first job was with the National Cash Register Company in Dayton. Then he and his father took a flyer--establishing the short-lived Midgley Tire & Rubber Company in Lancaster. The enterprise was not a success but it left Tom with a life-long interest in rubber--and in chemistry. Years later (and well before the critical, wartime need) he did tremendously significant work toward developing synthetic rubber. He was working at the time for the General Motors Chemical Company.

In 1916 he joined Charles Kettering at General Motors Research. It was to be a lifelong association and “Boss Ket" shares the glory for some of Tom's greatest developments. Tom's two most celebrated (and personally profitable) inventions were tetraethyl lead additive to make the familiar. Ethyl gasoline and freon, the first safe refrigerant. In his short career he was granted more than 100 patents, including one for extracting bromine from sea water--to break a bottleneck in the production of Ethyl gasoline. He was showered with professional honors. He became president of the American Chemical Society, received honorary doctorates from two universities and won five important medals for scientific achievement.

The house Thomas Midgley built, and my grandparents purchased in 1945.

In 1929 he came back to Columbus. Up along Wilson Bridge Road, between High Street and the Olentangy River Road he built a stately Colonial home. In spite of its immense size be installed a complete air-conditioning system, perhaps not the first such in all the land. He intended it for a retirement home for his father but made it his own home, too. He was there very little, dividing most of his time between Dayton, Detroit, Washington and New York.

The house was hardly completed when the great depression began. Midgley hired as many men as he could possibly use, building roads, landscaping and otherwise furbishing his estate. But, finally, everything was complete. The distress of the jobless still worried him. Then he had his great idea.

He had shared with most boys a feeling of fascination for caves. As he cast about for ways to make work, the old lure beckoned. The very immersity of what he envisioned was its chief advantage. It would take a lot of men a long time to dig and line with stone a system of caverns and rooms ranging inside the big bluff behind his house. And it would take a lot of money, which Midgley had. He lost no time getting on with the project.

Ted Severance, who now lives on nearby Worthington-Galena Road, was Midgley's estate manager. He became superintendent of what a lot of people thereabout considered the craziest project of all time. Some of them criticized Midgley for pouring good money into a "gigantic anthill." But most were gratefully aware that it was Tom's way of sharing his wealth--that the cavern was, in truth, a byproduct.

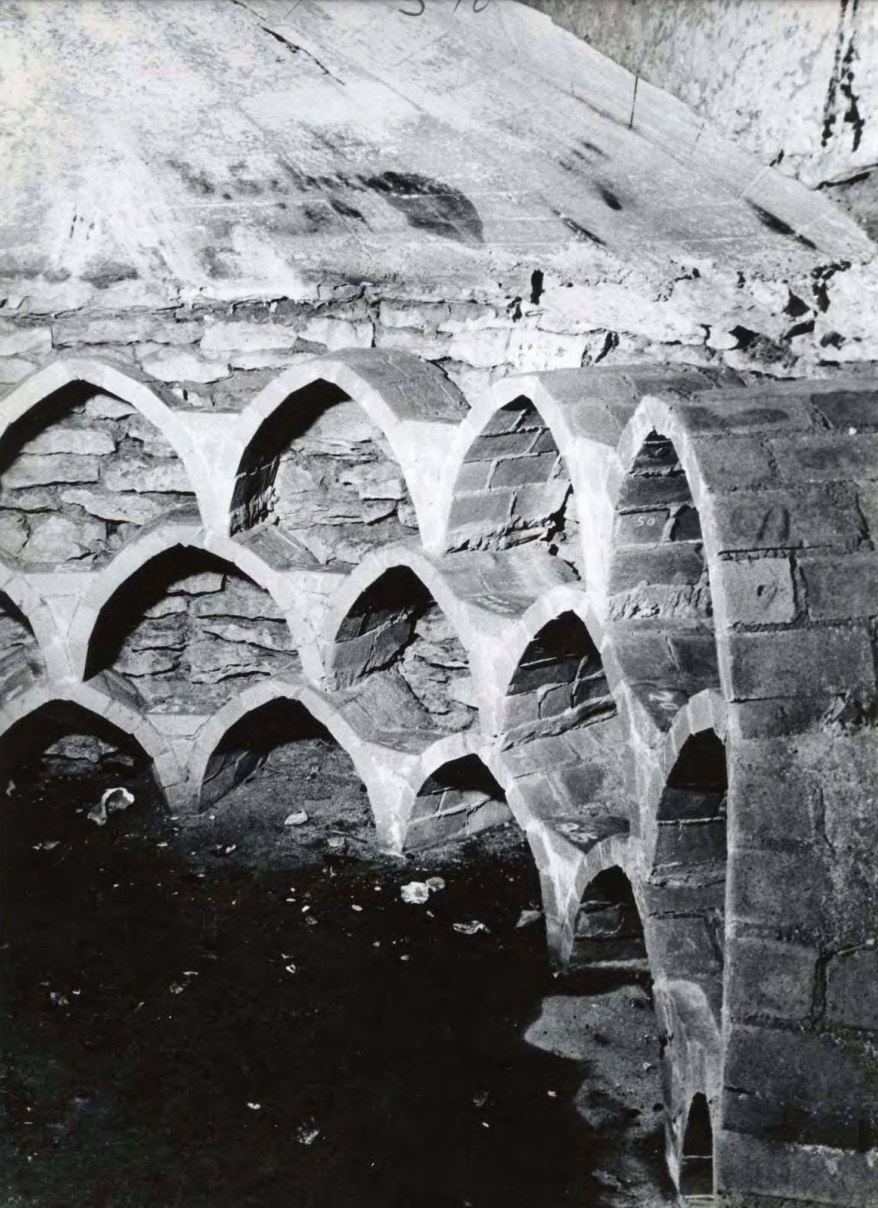

Ted recalls that the job took more than a year to complete, and that as many as 50 men at a time burrowed and dug to create two separate caverns (that were finally joined) and special rooms. The vaulted ceilings, the walls and floors were all built of limestone, blue and white, from nearby quarries. Ted and his father laid it all with meticulous care. The wrought-iron hardware – hinges, straps, bolts and candle sconces--were made by Mr. Kirker, a skilled Worthington blacksmith. At last the great undertaking was completed and things were back to normal.

Tom Midgley, it is said, got his money's worth out of the astonishment of his guests. It was his custom to invite them to the baronial-size recreation room and then swing open a heavy door at one end. Inside was a stone-lined room with a candle guttering in a grinning skull. With guests trailing in open mouthed wonder, he'd lead the way through another great door and, via vaulted passageways and endless steps, start the tour by candlelight. Visitors from all parts of the world came away wondering if they had really seen it or only dreamed of those tombless catacombs beneath peaceful Ohio soil.

Midgley continued his ceaseless professional activities until suddenly, in 1940, he contracted polio. Soon his legs were practically useless. Even so he continued to be the scientist. In 1942 he addressed the National Inventors' Council on behalf of the war effort from his home, via closed-circuit radio. For himself he invented a system of harness and slings so that he could move from bed to wheelchair with the strength of his arms. It was his final and fatal invention.

Thursday morning, November 2, 1944, his wife found him strangled by his own device. Thomas Midgley died at 55.

In 1945, the beautiful Midgley estate was purchased by Mr. and Mrs. Gail Winegarner. They had fallen in love with its spacious grounds and house but, even more importantly, they saw in it the perfect place to raise their five active sons. It has proved to be everything they desired.

More than a year ago I was passing the estate and, on sudden impulse, drove back its long, curving driveway to the house. I was received most kindly by Mr. Winegarner. I told him how much I always admired the place and said I'd like to make a painting of it. To my dismay he answered that I'd have to get on with it; that it would all be destroyed when the north Outerbelt went through. The distressing news brought to my mind the never personally confirmed story of the caves. Somewhat diffidently I asked if the famous “catacombs” really did exist. He assured me that they did and asked me if I'd like to inspect them. I jumped at the chance.

The pictures tell of what I saw. But they can't possibly convey the weird and wonderful sensation it was to step from the brilliantly lighted home into a gloomy cave, lighted by a glinting electric torch ahead, with inky blackness closing in behind. We traversed all of its many levels and explored all the passageways and rooms before returning to the house. Once there I asked eagerly if I might do a story about the caves for The Sunday Magazine. Mr. Winegarner smiled a rueful smile and said, “Not until the bulldozers are at our door." Then he explained why: Years ago the Winegarners became aware that the huge door to the cave at the foot of the bluff had been forced. They learned it by investigating noises from the caverns. They learned that boys (strong, well equipped boys) had been unable to resist the challenge of thię mysterious door. It developed that they had grown bolder and bolder, roistering in the caves and even trying to force their way into the house. A final blow came during a court hearing. It concerned a youthful gang that was accused of stealing. There was testimony that the gang had made the cave their headquarters and had hidden their loot in it.

Stronger bars on the bottom door didn't stop the intrusions. It was literally destroyed. The best estimate Mr. Winegarner could get for building a duplicate was $400. And then the bidder backed out.

Determined to stop the prowling, the Winegarners closed the lower entrance with a masonry wall. To their utter amazement and chagrin, the new wall was attacked with crowbars and sledgehaṁmers before the mortar was dry and soon pulled down. A second and far more formidable wall, at last, foiled the would-be trespassers. Not long afterward the family investigated noises down in the ravine and discovered evidence that an especially determined gang had been attempting to blast through the new wall. The presence of the alluring novelty became a real tribulation.

When Jack Hutton and I returned to the cave to take these pictures, Mrs. Winegarner added a new chapter to the vandalism saga. Quite recently she smelled smoke in the house and traced it to the rapidly filling recreation room. She then discovered that a second level door to the cave, halfway up the bluff had been forced (the door literally torn from its hinges) and that kids had built a roaring fire in one of the passageways. She insisted that a deputation of them come up to the house and see what was happening to the smoke.

With the second door gone, uninvited visitors have prowled the caves at all hours. Jack and I noted, just inside the forced entrance, a cache of matches and candles tucked between the stones. The Winegarners, before final destruction of the house, almost gave up trying to keep out trespassers; their concern being the danger of someone's being hurt. For that reason, primarily, they wanted no further publicity for the catacombs before roadwork began.

I could, of course, understand their feeling. Thus I kept my peace until now. The bulldozers will have started laying bare Tom Midgley's caverns by the time this appears in print and one of the strangest examples of privately financed welfare projects will be gone for good.