Odd Fellows Cemetery, 1900s. (wnp15.208; Courtesy of a Private Collector).

Writing a book is always an imperfect process. Most authors do our best to get all our facts straight before a book goes to press, but frequently find out later that we got something wrong, or didn’t have all of the information we needed.

I’ve learned a few such tidbits since “San Francisco’s Forgotten Cemeteries: A Buried History” came out almost 6 months ago, and thought it would be fun to share them here.

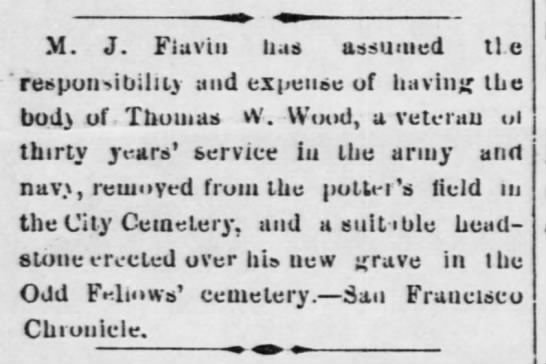

In the chapter on City Cemetery (where the Lincoln Park Golf Course and the Legion of Honor Museum operate today), I wrote about Thomas Wood, a military man who served in the Mexican-American War before taking his own life in San Francisco in early 1882. I — and other local cemetery historians — assumed Wood’s grave remained at City Cemetery to this day.

Clipping: The Arizona Sentinel, Yuma, Arizona, 04 Mar 1882.

However, another researcher, Alex Ryder, recently discovered that after the San Francisco Call wrote about Wood and the sad state of affairs at City Cemetery in February 1882, Wood’s body was exhumed and reburied in the Odd Fellows Cemetery, on the western slope of Lone Mountain. At the time, this would have been seen as a more respectable spot for a veteran than the Potter’s Field at the desolate edge of the city. But it probably wasn’t Wood’s last move. The Odd Fellows Cemetery was largely dug up and relocated to a plot in Colma’s Greenlawn Cemetery in 1932.

We know that at least a handful of Odd Fellows graves were left behind, but most of its 26,000 occupants now rest in Colma. Unfortunately, their plot has, in the past 100 years, been separated from the rest of Greenlawn by a large Best Buy retail store and parking lot. Before that, a United Artists 6 movie theater sat on the same site.

Today, the Odd Fellows reburial site is a weedy, fenced-off lot with a single, broken monument commemorating about as many dead as the population of El Cerrito or Eureka. In my book, I wrote that they were all in a single mass grave. I’ve since learned that the Odd Fellows remains were reburied carefully, each one with a small marker with some identifying information on it. Unfortunately, those markers have since been broken or moved, making it difficult to determine who is buried where.

Thomas Wood might have had an easier rest if he’d been left in City Cemetery.

Jewish Cemeteries, on the land that’s Dolores Park today.

I also reported in the book, based on faulty source material, that the Jewish cemeteries in today’s Dolores Park contained about 600 graves, but that wasn’t correct. It turns out they held somewhere between 3,500 and 5,000 graves. All those graves are now in Colma, as far as anyone knows. Thanks to Judi Leff for the correction.

Lastly, this isn’t so much a correction as a nifty connection. In the section on Sailor’s Burying Ground, one of San Francisco’s earliest settler cemeteries, I write about British seaman James Anderson, who died aboard the USS Congress in July 1847 and was buried in Sailor’s the next time the Congress docked in San Francisco.

This wasn’t the Congress’ first time in San Francisco; it wasn’t even the first Congress. This second iteration, built in Maine in 1842, was the flagship of the Mexican-American war from 1846 to 1848, a conflict that ties Thomas Wood, James Anderson, and many other newcomers to San Francisco together. Back to my point: Nine months earlier, the Congress docked in San Francisco, in October 1846, to bring California’s new Governor, Robert F. Stockton, to visit the tiny village of Yerba Buena on the shores of San Francisco Bay. Stockton was also the Commodore of the Congress from July 1846 until his retirement from the U.S. Navy in 1850, making it possible that he and James Anderson crossed paths, or even that they were on board together when Anderson died.

The Congress, for her part, served as a flagship in Brazil before joining the Union Army during the Civil War. She met her end in March 1862; while anchored off the coast of Virginia, she was attacked by the Confederate USS Virginia. She slipped her moorings, ran aground, and was destroyed by the ensuing fire and explosions. Governor Stockton died in Princeton, New Jersey, in October 1866, and is buried in Princeton Cemetery.