Puritan lawyer and politician John Winthrop.

One of the fun things about tracing one’s family tree is occasionally coming across well-known people who shaped our cultural history in some way. Of course, you have to be careful; genealogy sites are full of crowdsourced information, much of it duplicated across family trees without fact-checking. But if you follow the actual documentation, occasionally you find you’re related to someone people write Wikipedia articles or even books about.

I discovered recently that D. is distantly related to Stephen Bachiler, who was D’s 10th great-grandfather. What first caught my attention was discovering that one of D’s ancestors was buried on Halloween, 1656, in the infamous Bedlam Burial Ground in London. I have deep interests in London, cemeteries and historical treatments for mental illness, so discovering something like this makes my brain all kinds of curious. But when I looked Bachilor up online, I learned a lot more.

Bachiler was born June 23, 1561, attended Oxford University and was one of its early graduates. In 1587 he became the vicar of Wherwell, Hampshire, England, but was kicked out in 1605 because he was too Puritanical for the changing tastes of the British monarchy. He married four times. The first was Ann Bates, in 1589; they had six children together, including Theodate Bachiler (D’s ninth great-grandmother), who married Christopher Hussey and became one of the early settlers of New Hampshire. Christian Weare became Bachiler’s second wife in 1623; she died three years later, and then he married Helena Mason in 1627. I’ll get to his fourth wife in a moment.

In 1630, Bachiler was a member of the Company of Husbandmen, in London. They formed the Plough Company and secured a 1,600-square-mile land grant in Maine. They named it Lygonia, after Lygonia for Cecily Lygon, mother of New England Council president Sir Ferdinando Gorges, and Bachiler was going to be its leader and minister. He and Helena sailed to North America in 1632 and landed in Massachusetts, but by then the plans to establish Lygonia had already been abandoned. Puritan lawyer and leader John Winthrop later said that once the Plough Company families arrived and got a look at the land for themselves, they didn’t like it and settled elsewhere.

Bachiler bounced around New England for several years, establishing a church in Lynn (then Saugus), Massachusetts, where he managed to piss off the Puritan theocracy in Boston, apparently because of "his contempt of authority” and some sort of church “scandal.” Back in England, Bachiler and his son Stephen were sued by a local clergyman after they allegedly wrote “scandalous verse” about him and had been singing these songs around the village. But the scandal in Massachusetts was over something that eventually became a core American value: the separation of church and state. From his early days in England, Bachiler called for a “holy house without ceremonies,” a church free from the state’s control. In October of 1632, Winthrop was the governor of the state (the literal opposite of a separation between church and state) and had Bachiler arraigned for his stance on the church and state issue, forbidding him from “exercising his gifts as a pastor … until some scandles be removed.”

Hester Prynne and Pearl before the stocks, from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel “The Scarlet Letter.”

Bachiler later moved to Newbury, New Hampshire, with Theodate and Christopher, where they established a plantation at Winnacunnet. Bachiler named the town Hampton when the town was incorporated in 1639, and is credited as its founder. In 1644, Bachiler was invited to become minister of a new church in Exeter, Massachusetts, but that fell through when the state’s General Court postponed the establishment of a new church there. He returned to New Hampshire, working as a missionary in Strawbery Banke (now Portsmouth) and, in 1648, he married Mary Beedle. Three years later, she was indicted and sentenced for adultery with a neighbor, potentially inspiring the character of Hester Prynne in “The Scarlet Letter.”

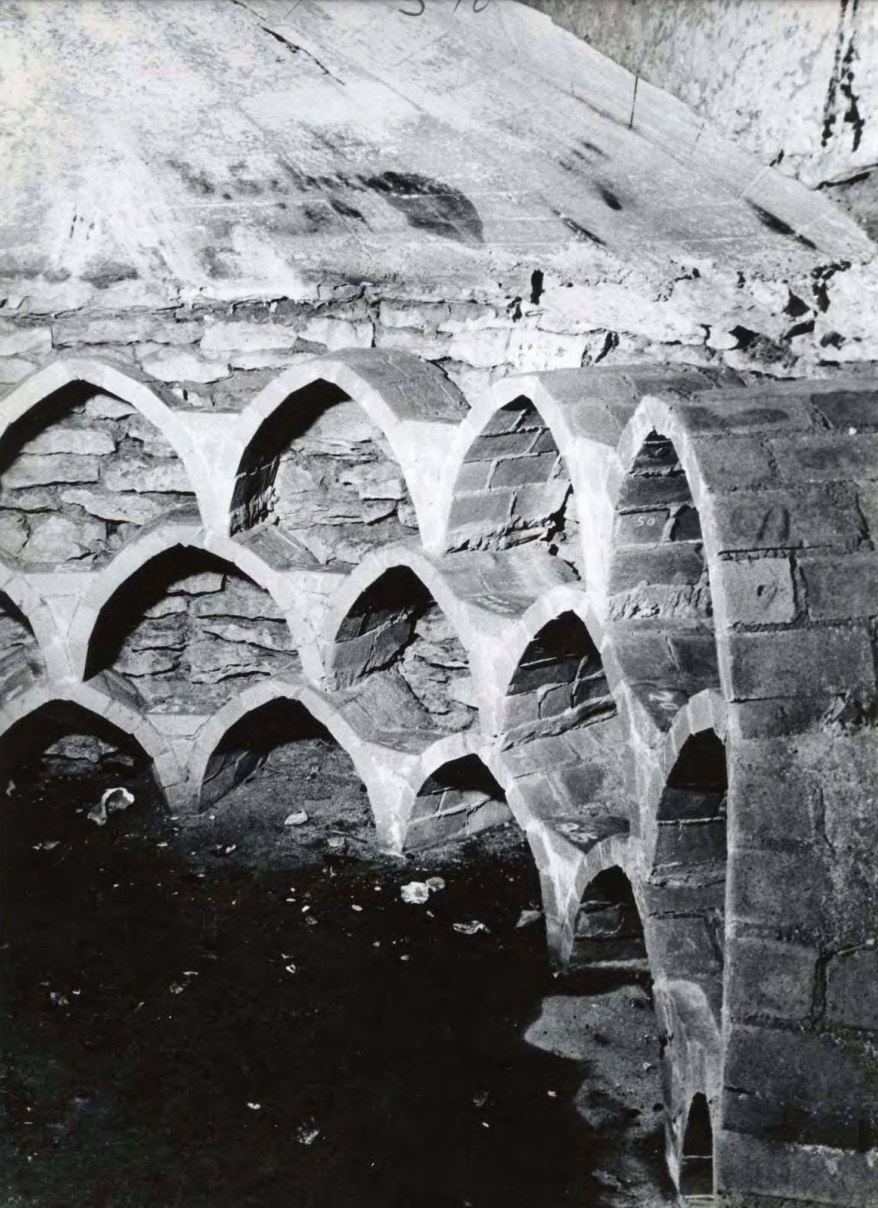

Even so, the courts would not grant Bachiler a divorce. He returned to England in 1653, where he died on Oct. 28, 1656. He was buried three days later in what was then called the New Churchyard, a municipal cemetery in London next door to Bethlem Hospital, known for housing and (debatably) caring for the mentally ill. An estimated 20,000 people were buried in this plot of land in the 16th and 17th centuries, but city development eventually overtook the area. Headstones were removed and a few graves were relocated, but many more remain. Today this cemetery is located beneath the Liverpool Street Crossrail station, about a half-mile north of the Tower of London.

If you enjoyed this and would like even more detail on the life of Stephen Bachiler, check out this 1961 article by Philip Mason Marston, Professor of History and Chairman of the Department at the University of New Hampshire.