Warning: This post includes mentions of abuse, suicide and abortion.

I must have been 14 or 15 the first time I heard Sinéad O’Connor’s voice, howling and crooning “Mandinka” from our television in the hours after school let out for the day. Her debut album was brave, challenging, feral. I wasn’t sure what to make of her, this bald-headed siren on the screen. But I never forgot her.

It was through interviews with O’Connor that I learned that abortion was illegal in the Republic of Ireland. Pregnant people who wanted not to be pregnant had to travel, and I knew, even then, that wasn’t possible for many people. When I heard the bare grief in “Three Babies,” in 1990, I assumed that’s what the song was about. (I didn’t learn until much later that it was about O’Connor’s miscarriages instead.)

Even so, that’s what went through my head when I watched her shred her mother’s photograph of Pope John Paul II that night on Saturday Night Live. In that moment, my chest filled with admiration — at her courage, at her willingness to put the Catholic Church in its place. And I was confused when she was crucified for it.

Many of us didn’t know then that the Catholic Church was lousy with sexually abusive clergy, and many others knew but thought hiding and denying it would keep it from being true. That was the real force behind O’Connor’s gesture, and even after the truth came out decades later, the world failed to adequately apologize to her.

O’Connor’s music came in and out of my life at key moments, including in 1997, when she released the “Gospel Oak” EP about a year and a half after my mom’s death. The whole album is a healing balm, in particular the opening song, “This Is To Mother You.” At the time, it felt like an umbilicus nourishing me from beyond the veil. Now, I suspect she wrote it in part for herself, to heal from the abuse she experienced at the hands of her mother when O’Connor was a child.

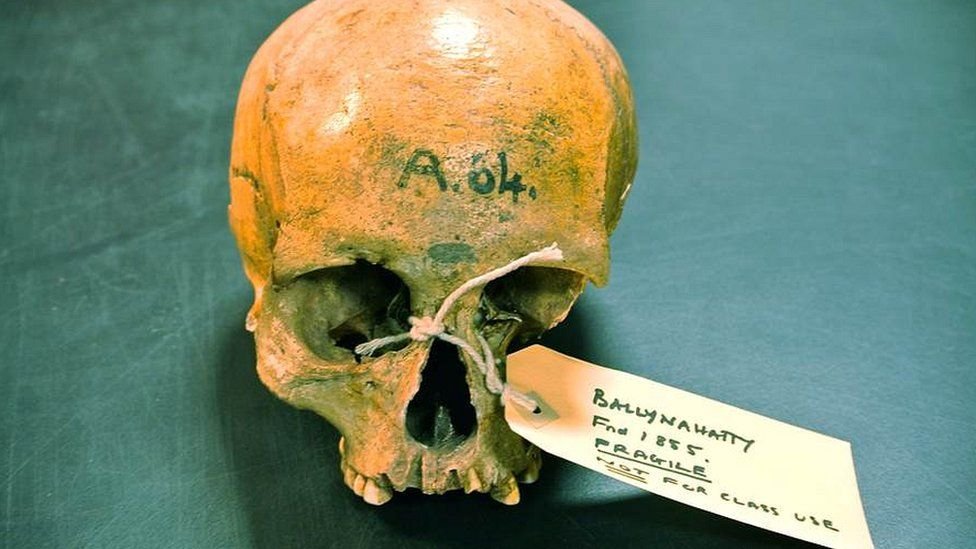

That abuse launched O’Connor into her life’s trajectory in so many ways; she went to live with her father at 13, but soon fell into risky behavior, including shoplifting, which landed her in a Magdalene asylum (laundry). Run by Catholic nuns, these institutions claimed to be “reform schools” at best, but functioned as prisons and labor farms for girls and women.

O’Connor was imprisoned in the An Grianán Training Centre, in northern Dublin, for 18 months. “We didn’t see our families, we were locked in, cut off from life, deprived of a normal childhood,” she told the Irish Times in 1993. “We were told we were there because we were bad people. … “We were girls in there, not women, just children really. And the girls in there cried every day.”

That experience contributed to her SNL protest, she said. “It wasn’t the only reason, but it was one of them.” The last of the Magdalene laundries in Ireland didn’t close until 1996.

I wasn’t raised Catholic, or even especially Christian. The Irish ancestors I know by name were Protestant, but I know I have others who were Catholic. They found great comfort in their faith, I can feel it in my bones. But they were also hurt by its restrictions, particularly for women and girls; I feel that, too. That’s part of why O’Connor’s protest ripped straight through me. It made me recognize a kindred spirit in her, even before I knew we both endured PTSD and mental illness, and would become mothers to suicidal children. That fury that rose up from her life and DNA? It was in mine, too.

Sinéad O’Connor was so much more than her trauma and pain. She was a stunning singer, a gutsy and honest songwriter, a woman daring enough to go about the world without her mask. The news of her death tore right through me, and through so many of us, as though we were no more than paper.

She said and did what so many others were afraid to. She was punished for it, and I can’t help but think she might have enjoyed a longer life if she hadn’t been. Today, the world is a little less brave, a little less honest, without her.