I recently discovered that GEDmatch allows you to match your DNA against samples from different “archaic” DNA finds, such as Ötzi or the Kennewick man. I thought it would be fun to try it and see what came up.

Before I talk about my results, let me first explain something about how DNA is measured. Bear with me.

There’s a unit of measure, the centimorgan*, that you may have heard if you’ve had your DNA analyzed by 23andMe, Ancestry or another service. According to Wikipedia, “One centimorgan corresponds to about 1 million base pairs in humans on average. The relationship is only rough, as the physical chromosomal distance corresponding to one centimorgan varies from place to place in the genome, and also varies between men and women since recombination during gamete formation in females is significantly more frequent than in males. Kong et al. calculated that the female genome is 4460 cM long, while the male genome is only 2590 cM long.”

I know that’s dense, but it’s helpful to understand, because services like 23andMe and GEDmatch figure out who you’re related to based on how much your DNA overlaps with others, and how long your matching segments are. For example, I share 50% of my DNA with my father, across 23 segments (the 23 chromosomes I inherited from him). In total, our shared segments are 3720cM long. By comparison, I share 10% of my DNA with one of my paternal cousins. She and I share 24 segments of DNA, but those shared segments total just 760cM.

As relations grow more distant, the number of shared segments – and, more significantly, the length of those segments – goes way down. This can be distance across the population (say, how closely related I might be to Kevin Bacon), or across time (how closely related I am to my 6th great-grandfather, Johannes Harbard Winegardner, who was born in Germany in 1718, immigrated to thee U.S. in 1752 and died in Virginia in 1779).

Any match below about 10 cM is dubious (Ancestry uses 8cM), less so if you can trace your and your match’s family tree back to a common ancestor. So the fact that GEDmatch begins matching your DNA against archaic samples at a threshold of .5cM should raise some eyebrows. But these matches allegedly don’t indicate direct lineage – a match with Ötzi doesn’t mean he’s your direct ancestor. Instead, it may just be chance, or it may indicate common migration patterns, meaning your ancestors lived in the same place, at roughly the same time, as these people whose remains we’ve sampled millennia later.

When I looked at my “Archaic DNA” matches at .5 cM, I had lots and lots of matches. Knowing they were dubious, I slowly increased the threshold until I still had some matches with several matching segments, and picked out several of those, the ones with the most overlaps, to research further. Here’s what I found, from oldest to most recent.

1. Ust-Ishim, Siberia, 45,000 years ago

This DNA comes from a femur found in western Siberia, and is the oldest genome for homo sapiens on record. It belonged to a male hunter-gatherer who likely descended from a group who left Africa more than 50,000 years ago to populate other regions, but later went extinct. About 2 percent of his genome came from Neanderthals. You can see an image of the femur here.

Bichon man’s skull. Picture by Y. André / Laténium. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

2. Bichon, Switzerland, 13,700 years ago

This DNA comes from the skull of a man found in the Grotte du Bichon, a cave in the Jura Mountains on the French-Swiss border. I love all the detail on this one. His bones were found “intermingled with the bones of a female brown bear, nine flint arrowheads and traces of charcoal.” Evidence suggests that the bear was wounded by arrows and retreated into the cave. The man followed, and made a fire to fumigate the bear from the cave, but was killed by the dying animal.

He belonged to the Western European hunter-gatherer lineage, based on comparisons to other fossils from the European mesolithic period. He was about 5-foot-five, 130 pounds, muscular, probably right handed, and had a mostly meat-based diet.

3. Kotias, Georgia, 9,700 years ago

This DNA comes from a man who was buried in Kotias Klde cave in the Caucasus Mountains of Georgia. He was one of a previously unknown group of hunter-gatherers in the Caucasus, and their DNA survives in many of today’s Europeans. He shares some DNA with the later Yamnaya culture across Europe, a semi-nomadic people known for burying their dead in pits with stelae and animal offerings, and often covered in ochre. You can see the Kotias skeleton here.

4. Loschbour, Luxembourg, 8,000 years ago

This man’s skeleton was found in 1835 under a rock shelter in Mullerthal, in eastern Luxembourg. He was part of European hunter-gatherer culture, and represented a transition between the dark skin of our African forebears and the light skin of many modern Europeans. His DNA reveals an “intermediate” skin tone, brown or black hair, and probably blue eyes. He was 5-foot-3, about 130 pounds, and was lactose-intolerant. He died in his mid-30s. Flint tools were found with his remains, and the cremated remains of another person, probably an adult woman, were found nearby. Her bones showed signs of scraping, suggesting that her bones were defleshed before burning. You can see the man’s skeleton here.

5. Stuttgart, Germany, 7,000 years ago

This DNA belonged to a person who was part of the Linearbandkeramik (Linear Pottery Ceramic) culture that was prominent in Germany during the Neolithic period. This culture – and this individual – were farmers, growing emmer and einkorn wheat, crab apples, peas, lentils, flax, poppies and barley. They raised some animals, including cows and sheep, and lived in small villages of longhouses near waterways.

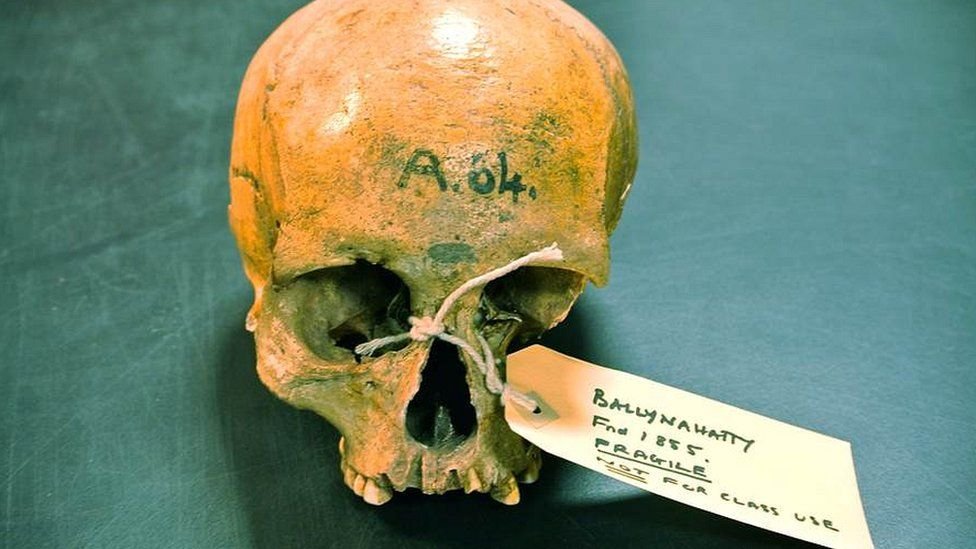

Skull of a Neolithic woman found in Ballynahatty, Northern Ireland.

6. Ballynahatty, Northern Ireland, 5,200 years ago

This DNA comes from the remains of a Neolithic woman found in a tomb chamber in Ballynahatty, near Belfast, in Northern Ireland. Her genes are similar to modern people from Spain and Sardinia, but her ancestors likely came to Europe from the Middle East. She was lactose-intolerant and carried a genetic variant for hemochromatosis, which can cause excessive iron retention.

7. Rathlin Island, Northern Ireland, 4,000 years ago

This DNA comes from one of two male skeletons found on Rathlin Island, just north off the coast of Northern Ireland. Unlike the woman found in Ballynahatty, these Bronze Age men could digest milk and their genetics are more aligned with modern Irish, Scottish and Welsh peoples. A third of their DNA came from ancient cultures who lived in the Pontic Steppe, a region now divided between Russia and Ukraine. Both men carried a variant for hemochromatosis, but a different one from the Ballynahatty woman. Ireland’s modern population has one of the highest frequencies of lactase persistence, as well as hemochromatosis. I’m partly Irish – 4%, according to Ancestry, and 79% British and Irish, according to 23andMe – and carry both of these variants.

If nothing else, this exploration has allowed me to learn more about some early DNA finds, as well as what they mean for the migration patterns of my ancestors before they turned into the Northwestern European residents I can trace through genealogical records. It’s fascinating, and as always, I’m tempted to visit some of these places to see what it feels like to stand on the same ground.

*Named after American biologist and geneticist Thomas Hunt Morgan, born in 1866, part of a line of Southern plantation owners and enslavers on his father's side. He was a nephew of Confederate General John Hunt Morgan.

Top photo: Linearbandkeramik Culture farmhouse, photographed by Hans Splinter. (CC BY-ND 2.0)