Content warning: brief discussion of suicide and child murder, spoilers for “Stranger Things” season 4.

Let’s get this out of the way: I love Eddie Munson, the charming metalhead teen introduced in the new season of “Stranger Things.” I was a teenager in the 1980s, too, and he reminds me of dear friends I had at that age. In some ways, I wanted to BE him, but I was too much of a “good girl” to try.

More than that, I love the story that stirs up around him, and how it turns the 1980s moral panics over Satanism, role-playing games and heavy metal upside down. I wrote about these panics in “The Columbine Effect,” in an effort to show that scapegoated teen pastimes are sources of community, creativity and solace. So it made me incredibly happy to see “Stranger Things” stump for them, too, particularly through Eddie.

On paper, it doesn’t seem like Eddie Munson should work as a character. His name alone is a collage of too-obvious cultural references: Eddie Van Halen, Eddie Munster, Charles Manson, and Eddie the mascot for Iron Maiden, whose music Eddie defends in the opening of season 4, episode 8. The Duffer brothers based him, in part, on Damien Echols, one of three teens sentenced to prison in 1993 after being wrongly convicted of murdering three young boys. Although prosecutors didn’t have any solid evidence against Echols and his friends, the fact that he studied witchcraft and liked Metallica in the midst of the Satanic Panic put a target on his back.

In “Stranger Things,” Eddie is a classic metalhead, adored by people who know him but misunderstood by everyone else. He wears his curly hair long, and his daily uniform includes a denim vest plastered with metal-band patches and a t-shirt advertising his Dungeons & Dragons group, The Hellfire Club. So when Chrissy Cunningham dies in his trailer – a victim of a demon attack – Eddie and his D&D- and metal-loving ways are immediately blamed.

But there’s a twist: we, the audience, know Eddie didn’t do anything wrong. We see the community whipping up frenzy around him – because they don’t know about the Upside Down, about its demon creatures, the Mind Flayer, or Vecna (himself originally a D&D character!), who are the real problems here.

To understand how people in the 1980s became so terrified of role-playing games, it helps to look at the history.

In 1979, James Dallas Egbert III, a student at Michigan State University, ran away from school with the intention of ending his life. He left behind a note mentioning the steam tunnels beneath the school, as well as Dungeons & Dragons. Local reporters claimed the game inspired him to run away. He returned, but the 16-year-old college prodigy faced unbearable stress and was allegedly battling a drug addiction. He succeeded in ending his life a year later. Many believed D&D was at least partly responsible.

Then, one June afternoon in 1982, Irving “Bink” Pulling, a 16- year-old resident of Montpelier, Virginia, took his family's loaded handgun and shot himself in the chest. His mother, Patricia Pulling, found him dead in the front yard. While going through her son's belongings, Pulling found a handful of Dungeons & Dragons books and asked around to find out what they were. At a local shop that sold role-playing supplies, she asked a clerk how she could learn more about the game. Eventually, she wound up connecting with a handful of gamers at a local college. They played D&D with her for more than a month, according to her book, “The Devil's Web.”

Bink's friends and teachers said he was suffering from depression, isolation, and instability. Despite this, Pulling became convinced that Dungeons & Dragons had made her son want to kill himself. In 1984 she founded Bothered About Dungeons & Dragons, or B.A.D.D., an organization she hoped would raise awareness about the supposed evils of role-playing games.

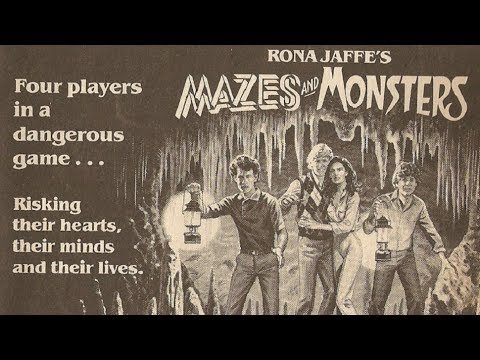

Egbert's story inspired a 1981 novel by Rona Jaffe, “Mazes and Monsters,” as well as a December, 1982, film starring Tom Hanks. In the movie, Hanks plays Robbie, a college student who joins his peers in a game of the fictional Mazes and Monsters RPG. He suffers a psychotic break while playing a live-action version in the caverns near their university. Robbie begins behaving like his M&M character in real life, and will only respond to the character's name. Disoriented, he treks to New York City in search of his estranged brother, and nearly dies by suicide. The movie added fuel to the idea that D&D puts its players in danger.

And in 1985, Newsweek ran a cover story on role-playing games, called “Kids: The Deadliest Game?” In “Stranger Things,” Eddie reads aloud from a similar Newsweek article and mocks it.

“If kids can believe in a god they can’t see,” Pulling told Newsweek, “then it’s very easy for them to believe in occult deities they can’t see.” In “Stranger Things,” there is a demon that many of the kids can see but the adults, for the most part, haven’t. After Vecna kills Chrissie and two other local kids, Eddie winds up on the receiving end of a massive manhunt, complete with locals stocking their arsenals at the local gun store and a catchy title for the crime spree: “The Munson Murders.”

But again, we see Eddie as nothing but kind, loyal and brave, fighting to protect the very same community that demonized him. His D&D crew becomes his real-life fighting party, and his love of heavy metal – displayed most vividly in a blistering performance of Metallica’s “Master of Puppets” while surrounded by a tornado of demobats – ultimately makes him a hero. Epic times call for epic music, and Eddie, like most metalheads, understands this implicitly even when society hates him for it.

In getting to know Eddie, a good-hearted character who’s devoted to D&D and metal, audiences can see how wrong we were in the ‘80s by sidelining guys like him, or worse – sending them to prison for two decades. Maybe, in the future, we can do better.